Wednesday, 11 December 2013

Saturday, 7 December 2013

Surprisingly, a Huff Post article I really dig

COOL GIRLS DIE ALONE

Amy Turner

Posted: 12/06/2013 3:01 pm

This essay was adapted from Amy Turner's forthcoming book, Cool Girls Die Alone, which is currently at publishers.

I used to hate entitled women -- skags who act like relationships and manicures are a birthright. As a child of the seventies, I grew up knowing one thing: I was entitled to a career, I was not entitled to a relationship.

Psychologist Esther Perel says, "Our sense of self-worth is connected to desire, because in order to want something, you need to feel entitled to it."

I'd spat that word in my head at rich kids growing up, having no idea the salvation that would come in reclaiming it. But before this happens, you can veer into territory that will lead you into a forest of fine leather goods and loneliness: the backwoods occupied by 'the cool girl.' Huddled around a fire, a hobo camp of trampers/girlswhoworkhard, warming their hands over embers of some dude who introduced them as a 'friend' at a family holiday, too ashamed to admit they want to feel as deserving of partnership as the do of making partner. She gets...cool. You don't have to smoke cigs and wear red lipstick like Rizzo to be cool (although it does help), you just stop admitting you want things.

Your poor wants. Maybe you poured whiskey on 'em, maybe you built a rolodex of punch lines, maybe you piled paychecks in a drawer hoping you could buy your way out. But tell me, why are women making six figures a year going into Anthrolpologie to buy a ruffled apron? Because there is something deep inside us that yearns to make home, and it is not shameful.

It took me 38 years to rid the word homemaker of shame. Sheryl Sandberg asked, "what would you do if you weren't afraid?" And my first impulse was to say, Sheryl, I would make a casserole.

I am not suggesting we time travel back to pot roast and no earning power. I am suggesting that we stop lying about the place in us that yearns to nurture and be nurtured.

Shame is the grandmother of cool. And once she wags her finger at you, instilling feelings of guilt, regret or sadness because you know you've done something wrong, she is a toughie to shake. Women get it in the kisser. We get it in special ways. We get it in our bodies, in our sexuality, in our earning power... our mating or lack there of.

I was shamed for not being married (a woman recently asked me, 'why are you still Amy Turner?'). The same day I was shamed for not being further along financially ('you haven't bought a house yet?') Nothing is safe.

But until we stand up to Grammy Shame and own that our wanting is not wrong, we are going to be afraid (see juice cleanses, high heeled sneakers, angel chain emails). Because in the wanting is that soft pink squishy part that is... vulnerable. And you may be self sufficient, you may be a top earner, you may have buttocks the size and shape of a grapefruit, but you will not have peace.

And somewhere after you buy the Chanel bag and before you jump off a cliff because you haven't Pinterest-ed a taffeta gingham flower girl, you will realize that peace, self-acceptance, and authenticity trump everything.

You have had spin class, an assistant, and a boyfriend who takes you to nice places (but not Kleinfeld's). You have worked hard, stayed busy, anything to avoid the hooks of shame because maybe... just a little bit... maybe... you used this busy-ness to stop you from creating a space in yourself where you felt nurtured. Because if felt nurtured, you'd stop trying? Or if you felt nurtured, you'd share that with someone, and you couldn't control how it would be received (you totally know how having no needs is received-the jerks you pick LOVE IT).

Cool girls like to be in control. Control kills intimacy. Hooray, cool and alone forever!

But, what if you make 'space' and wake up a soft loser? What if you wake up an unemployed girl in a pale yellow dress taking vacations with her parents on trains? What if... you accept that you can't make a home for a family because you've refused to make a home for yourself. That home is a state of mind, not a spongecake. That you can buy the apron. But it won't matter until you build a place in yourself that is soft.

Lean into that.

I don't see women who are afraid of work; I see women only knowing their value through work. There is a place that honors you for your femininity, but you have to build it. Nobody told me that. So I am telling you, friend.

Spackle your worth in something besides your work in the cracks. Lay down wall-to-wall compassion, hang some kindness and put the idea that you are deficient in some way on dimmers.

And I could be wrong, but I think that's how you get to the next home. The one you share with someone. The one where you put on that apron, should you desire. Work is great, but there were no suffragettes for the human heart, and cool girls... cool girls die alone.

Friday, 29 November 2013

Thursday, 28 November 2013

The Golden Age

Oh you don't known Woodkid is? Well I'm about to tell you because you should.

Born Yoann Lemoine, Woodkid, is an amzing illustartor and film director. He's directed some badass music videos including Lana Del Rey's Born to Die

And then all of a sudden, Lemoine started making his very own soundtracks.

Case in point: this short film he directed for Lolita Lempicka LeParfum featuring the delectable Elle Fanning.

And now is he is a fucking badass solo artist. ALSO DID I MENTION THAT HE IS FRENCH. RWOAR!

His first hit is Iron, from the EP of the same name. It was famouslly used in the Assassin's Creed video game and the music video features superscmodel Agyness Deyn weilding a bird of prey. Obvs he makes all his own videos.

And then came the second EP. All his music so far has addressed this grand coming of age narrative about a little boy and his videos portray the plot. Can you see my heart crumble?

This year Woodkid released his debut LP, called the Golden Age (melt). I Love You was the first single off the album and one of my favourite tracks.

Oh, and he's touring. He has super theatrical shows with a full orchestra and heaps of audiovisuals and lasers and shit. Oh, and he's still making new music: this is his latest composition.

Oh, and did I forget to mention that Lana Del Rey is his muse?

Here they are singing Video Games together.

Sex.

Born Yoann Lemoine, Woodkid, is an amzing illustartor and film director. He's directed some badass music videos including Lana Del Rey's Born to Die

And then all of a sudden, Lemoine started making his very own soundtracks.

Case in point: this short film he directed for Lolita Lempicka LeParfum featuring the delectable Elle Fanning.

And now is he is a fucking badass solo artist. ALSO DID I MENTION THAT HE IS FRENCH. RWOAR!

His first hit is Iron, from the EP of the same name. It was famouslly used in the Assassin's Creed video game and the music video features superscmodel Agyness Deyn weilding a bird of prey. Obvs he makes all his own videos.

And then came the second EP. All his music so far has addressed this grand coming of age narrative about a little boy and his videos portray the plot. Can you see my heart crumble?

This year Woodkid released his debut LP, called the Golden Age (melt). I Love You was the first single off the album and one of my favourite tracks.

Oh, and he's touring. He has super theatrical shows with a full orchestra and heaps of audiovisuals and lasers and shit. Oh, and he's still making new music: this is his latest composition.

Oh, and did I forget to mention that Lana Del Rey is his muse?

Here they are singing Video Games together.

Sex.

Casual Adele cover. No biggie.

And now this is coming.

And now this is coming.

I cannot bloody wait.

I Share Therefore I Am

I am a social media addict.

I really don't like what this video is saying. That doesn't make it untrue (or true for that matter). I just really don't like what it's saying.

I really don't like what this video is saying. That doesn't make it untrue (or true for that matter). I just really don't like what it's saying.

Tuesday, 26 November 2013

Miley And Her Virtual Kitten Won The AMAs, The Internet, Life

And Miley is standing in front of this adorable kitten singing her heart out.

And looking awesome because she’s Miley and she rocks.

AND she’s wearing a cool two-piece thing with CATS ON IT.

So she’s singing in a cat outfit with a giant kitten behind her and cool space graphics and everything is great.

And this kitten moves its mouth trying to sing.

So while Miley is singing this kitten is just, like, going “blahslhkdhlkghl” because it’s a cat and can’t really sing and it’s adorable.

And the kitten’s eyes also get all wide and cute and Miley is emotional and then we are all like omggggggg this is too much.

And then, as if “Wrecking Ball” wasn’t getting to you enough, the kitten starts CRYING.

Full tears come from the kitten and it’s heartbreaking.

And just when Miley is belting out the last bit of the song, and the kitten is staring at you…

THIS HAPPENS.

Sekgjrnkhjnsltrjkhnrk

And then it’s over and you realize why Miley is Miley.

Monday, 25 November 2013

The Enclave

I this was my absolute favourite work at the Venice Biennale this year.

Richard Mosse's The Enclave was eerie and dreamy and beautiful and fucking disturbing because the violence captured just looked so beautiful.

A friend of mine who has experience with shooting (she grew up in Soviet Russia and learned how to shoot in school) explained that the incongriuity in perspective created by the way the multiple video screens were installed, reminded her of looking down the barrel of a rifle.

Richard Mosse's The Enclave was eerie and dreamy and beautiful and fucking disturbing because the violence captured just looked so beautiful.

A friend of mine who has experience with shooting (she grew up in Soviet Russia and learned how to shoot in school) explained that the incongriuity in perspective created by the way the multiple video screens were installed, reminded her of looking down the barrel of a rifle.

If We’re Doing All The “Right” Things, Why Are We Still Unemployed?

I am not an economist. But it doesn’t take an

economist to realize that something is wrong with the economy. It

doesn’t take an economist to realize that high unemployment is becoming a new standard,

five years after the great crash of 2008. It doesn’t take an economist

to realize that underemployment is becoming the new unemployment. And it

doesn’t take an economist to realize that all of this is becoming the

new normal.

Normal. 7.3% unemployment is normal. 14.3% underemployed and unemployed is normal. Yes. It is. At least for my generation.

That is depressing.

I realize I’m speaking from a position of privilege,

someone who got a college degree, and didn’t have to dive deep into debt

to do it. Someone who is currently getting their master’s degree thanks

to fellowships and TA-ships. I grew up middle class. I’m also white and

cis-gender.

I’m also aware of the fact that when I graduate in a year,

with a master’s degree and a teaching license, I will be fighting

tooth-and-nail for a job. I fully expect to send out upwards of 50

applications if I want to get one interview. And I’m scared shitless at

the prospect that a year after I graduate with those degrees, I might

still be unemployed.

Circumstance forces me to admit that I am one of the lucky ones.

And yet, the word “lucky” has a bitter taste of irony.

Because in the same city where students are being squeezed into

classrooms that don’t serve them, there have been 51 schools closed and

2,100 teachers laid off this year alone.

People tell me that I was silly to get a major in the

humanities. Which is why I’m getting a teaching license. They tell me

that I should have had a better plan. Except that this was my better

plan – my original dream was to be a living history interpreter, which

pays hourly. (Previous dreams included figure skater, singer, and

writer, respectively. Society talked me out of them all.) They tell me

that I should have had fail-safe career. Isn’t public education – an

industry that our society is built on, and will always need – fail-safe?

I’m tired of being told that I should have been a STEM

major. We can’t all be. We shouldn’t all be. This country, counter to

current myth, is not going to shrivel up and die for lack of science and

math folks. And what’s more, a STEM major doesn’t guarantee a job like

the conventional wisdom says it does. 9% of computer science recent grads are unemployed and only 6% of theater majors are searching for jobs.

I’m tired of some careers being ranked as “smart” and

“practical” and others being ranked as “stupid decisions.” I’m tired of

different types of people being cast as “marketable” and others as “worthless.”

I’m tired of various work being deemed to have more value than other

work. I’m tired of being told by the older generations that we’re just

not working hard enough, and we expect to have it all. I never thought I

would have it all. But I did think that I would have half a shot at

getting a full-time job when I graduated with a B.A.

It’s all backwards. It’s all wrong. And yet, wrong and backwards are the new norm.Written by Laura Koroski

Accessed at Feminspire

Art Makes You Smart

Alain Pilon

By BRIAN KISIDA, JAY P. GREENE and DANIEL H. BOWEN

Published: November 23, 2013

FOR many education advocates, the arts are a panacea: They supposedly

increase test scores, generate social responsibility and turn around

failing schools. Most of the supporting evidence, though, does little

more than establish correlations between exposure to the arts and

certain outcomes. Research that demonstrates a causal relationship has

been virtually nonexistent.

A few years ago, however, we had a rare opportunity to explore such relationships when the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

opened in Bentonville, Ark. Through a large-scale, random-assignment

study of school tours to the museum, we were able to determine that

strong causal relationships do in fact exist between arts education and a

range of desirable outcomes.

Students who, by lottery, were selected to visit the museum on a field

trip demonstrated stronger critical thinking skills, displayed higher

levels of social tolerance, exhibited greater historical empathy and

developed a taste for art museums and cultural institutions.

Crystal Bridges, which opened in November 2011, was founded by Alice

Walton, the daughter of Sam Walton, the founder of Walmart. It is

impressive, with 50,000 square feet of gallery space and an endowment of

more than $800 million.

Thanks to a generous private gift, the museum has a program that allows

school groups to visit at no cost to students or schools.

Before the opening, we were contacted by the museum’s education

department. They recognized that the opening of a major museum in an

area that had never had one before was an unusual event that ought to be

studied. But they also had a problem. Because the school tours were

being offered free, in an area where most children had very little prior

exposure to cultural institutions, demand for visits far exceeded

available slots. In the first year alone, the museum received

applications from 525 school groups requesting tours for more than

38,000 students.

As social scientists, we knew exactly how to solve this problem. We

partnered with the museum and conducted a lottery to fill the available

slots. By randomly assigning school tours, we were able to allocate

spots fairly. Doing so also created a natural experiment to study the effects of museum visits on students, the results of which we published in the journals Education Next and Educational Researcher.

Over the course of the following year, nearly 11,000 students and almost

500 teachers participated in our study, roughly half of whom had been

selected by lottery to visit the museum. Applicant groups who won the

lottery constituted our treatment group, while those who did not win an

immediate tour served as our control group.

Several weeks after the students in the treatment group visited the

museum, we administered surveys to all of the students. The surveys

included multiple items that assessed knowledge about art, as well as

measures of tolerance, historical empathy and sustained interest in

visiting art museums and other cultural institutions. We also asked them

to write an essay in response to a work of art that was unfamiliar to

them.

These essays were then coded using a critical-thinking-skills assessment

program developed by researchers working with the Isabella Stewart

Gardner Museum in Boston.

Further, we directly measured whether students are more likely to return

to Crystal Bridges as a result of going on a school tour. Students who

participated in the study were given a coupon that gave them and their

families free entry to a special exhibit at the museum. The coupons were

coded so that we could determine the group to which students belonged.

Students in the treatment group were 18 percent more likely to attend

the exhibit than students in the control group.

Moreover, most of the benefits we observed are significantly larger for

minority students, low-income students and students from rural schools —

typically two to three times larger than for white, middle-class,

suburban students — owing perhaps to the fact that the tour was the

first time they had visited an art museum.

Further research is needed to determine what exactly about the

museum-going experience determines the strength of the outcomes. How

important is the structure of the tour? The size of the group? The type

of art presented?

Clearly, however, we can conclude that visiting an art museum exposes

students to a diversity of ideas that challenge them with different

perspectives on the human condition. Expanding access to art, whether

through programs in schools or through visits to area museums and

galleries, should be a central part of any school’s curriculum.

Brian Kisida is a senior research associate and Jay P. Greene is a professor of education reform at the University of Arkansas. Daniel H. Bowen is a postdoctoral fellow at the Kinder Institute of Rice University.

Acessed at The New York Times

Acessed at The New York Times

Monday, 6 May 2013

Saturday, 27 April 2013

Michel Foucault's OF OTHER SPACES

The great obsession of the nineteenth century was, as we know, history: with its themes of development and of suspension, of crisis, and cycle, themes of the ever-accumulating past, with its great preponderance of dead men and the menacing glaciation of the world. The nineteenth century found its essential mythological resources in the second principle of thermaldynamics. The present epoch will perhaps be above all the epoch of space. We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed. We are at a moment. I believe, when our experience of the world is less that of a long life developing through time than that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein. One could perhaps say that certain ideological conflicts animating present-day polemics oppose the pious descendents of time and the determined inhabitants of space. Structuralism, or at least which is grouped under this slightly too general name, is the effort to establish, between elements that could have been connected on a temporal axis, an ensemble of relations that makes them appear as juxtaposed, set off against one another, implicated by each other—that makes them appear, in short, as a sort of configuration. Actually, structuralism does not entail denial of time; it does involve a certain manner of dealing with what we call time and what we call history.

Yet it is necessary to notice that the space which today appears to form the horizon of our concerns, our theory, our systems, is not an innovation; space itself has a history in Western experience, and it is not possible to disregard the fatal intersection of time with space. One could say, by way of retracing this history of space very roughly, that in the Middle Ages there was a hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane plates: protected places and open, exposed places: urban places and rural places (all these concern the real life of men). In cosmological theory, there were the supercelestial places as opposed to the celestial, and the celestial place was in its turn opposed to the terrestrial place. There were places where things had been put because they had been violently displaced, and then on the contrary places where things found their natural ground and stability. It was this complete hierarchy, this opposition, this intersection of places that constituted what could very roughly be called medieval space: the space of emplacement.

This space of emplacement was opened up by Galileo. For the real scandal of Galileo's work lay not so much in his discovery, or rediscovery, that the earth revolved around the sun, but in his constitution of an infinite, and infinitely open space. In such a space the place of the Middle Ages turned out to be dissolved. as it were; a thing's place was no longer anything but a point in its movement, just as the stability of a thing was only its movement indefinitely slowed down. In other words, starting with Galileo and the seventeenth century, extension was substituted for emplacement.

Today the site has been substituted for extension which itself had replaced emplacement. The site is defined by relations of proximity between points or elements; formally, we can describe these relations as series, trees, or grids. Moreover, the importance of the site as a problem in contemporary technical work is well known: the storage of data or of the intermediate results of a calculation in the memory of a machine, the circulation of discrete elements with a random output (automobile traffic is a simple case, or indeed the sounds on a telephone line); the identification of marked or coded elements inside a set that may be randomly distributed, or may be arranged according to single or to multiple classifications.

In a still more concrete manner, the problem of siting or placement arises for mankind in terms of demography. This problem of the human site or living space is not simply that of knowing whether there will be enough space for men in the world —a problem that is certainly quite important — but also that of knowing what relations of propinquity, what type of storage, circulation, marking, and classification of human elements should be adopted in a given situation in order to achieve a given end. Our epoch is one in which space takes for us the form of relations among sites.

In any case I believe that the anxiety of our era has to do fundamentally with space, no doubt a great deal more than with time. Time probably appears to us only as one of the various distributive operations that are possible for the elements that are spread out in space,

Now, despite all the techniques for appropriating space, despite the whole network of knowledge that enables us to delimit or to formalize it, contemporary space is perhaps still not entirely desanctified (apparently unlike time, it would seem, which was detached from the sacred in the nineteenth century). To be sure a certain theoretical desanctification of space (the one signaled by Galileo's work) has occurred, but we may still not have reached the point of a practical desanctification of space. And perhaps our life is still governed by a certain number of oppositions that remain inviolable, that our institutions and practices have not yet dared to break down. These are oppositions that we regard as simple givens: for example between private space and public space, between family space and social space, between cultural space and useful space, between the space of leisure and that of work. All these are still nurtured by the hidden presence of the sacred.

Bachelard's monumental work and the descriptions of phenomenologists have taught us that we do not live in a homogeneous and empty space, but on the contrary in a space thoroughly imbued with quantities and perhaps thoroughly fantasmatic as well. The space of our primary perception, the space of our dreams and that of our passions hold within themselves qualities that seem intrinsic: there is a light, ethereal, transparent space, or again a dark, rough, encumbered space; a space from above, of summits, or on the contrary a space from below of mud; or again a space that can be flowing like sparkling water, or space that is fixed, congealed, like stone or crystal. Yet these analyses, while fundamental for reflection in our time, primarily concern internal space. I should like to speak now of external space.

The space in which we live, which draws us out of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives. our time and our history occurs, the space that claws and gnaws at us, is also, in itself, a heterogeneous space. In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.

Of course one might attempt to describe these different sites by looking for the set of relations by which a given site can be defined. For example, describing the set of relations that define the sites of transportation, streets, trains (a train is an extraordinary bundle of relations because it is something through which one goes, it is also something by means of which one can go from one point to another, and then it is also something that goes by). One could describe, via the cluster of relations that allows them to be defined, the sites of temporary relaxation —cafes, cinemas, beaches. Likewise one could describe, via its network of relations, the closed or semi-closed sites of rest — the house, the bedroom, the bed, el cetera. But among all these sites, I am interested in certain ones that have the curious property of being in relation with all the other sites, but in such a way as to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect. These spaces, as it were, which are linked with all the others, which however contradict all the other sites, are of two main types.

HETEROTOPIAS

First there are the utopias. Utopias are sites with no real place. They are sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces.

There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places — places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society — which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias. I believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.

As for the heterotopias as such, how can they be described? What meaning do they have? We might imagine a sort of systematic description — I do not say a science because the term is too galvanized now —that would, in a given society, take as its object the study, analysis, description, and "reading" (as some like to say nowadays) of these different spaces, of these other places. As a sort of simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live, this description could be called heterotopology.

Its first principle is that there is probably not a single culture in the world that fails to constitute heterotopias. That is a constant of every human group. But the heterotopias obviously take quite varied forms, and perhaps no one absolutely universal form of heterotopia would be found. We can however class them in two main categories.

In the so-called primitive societies, there is a certain form of heterotopia that I would call crisis heterotopias, i.e., there are privileged or sacred or forbidden places, reserved for individuals who are, in relation to society and to the human environment in which they live, in a state of crisis: adolescents, menstruating women, pregnant women. the elderly, etc. In out society, these crisis heterotopias are persistently disappearing, though a few remnants can still be found. For example, the boarding school, in its nineteenth-century form, or military service for young men, have certainly played such a role, as the first manifestations of sexual virility were in fact supposed to take place "elsewhere" than at home. For girls, there was, until the middle of the twentieth century, a tradition called the "honeymoon trip" which was an ancestral theme. The young woman's deflowering could take place "nowhere" and, at the moment of its occurrence the train or honeymoon hotel was indeed the place of this nowhere, this heterotopia without geographical markers.

But these heterotopias of crisis are disappearing today and are being replaced, I believe, by what we might call heterotopias of deviation: those in which individuals whose behavior is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm are placed. Cases of this are rest homes and psychiatric hospitals, and of course prisons, and one should perhaps add retirement homes that are, as it were, on the borderline between the heterotopia of crisis and the heterotopia of deviation since, after all, old age is a crisis, but is also a deviation since in our society where leisure is the rule, idleness is a sort of deviation.

The second principle of this description of heterotopias is that a society, as its history unfolds, can make an existing heterotopia function in a very different fashion; for each heterotopia has a precise and determined function within a society and the same heterotopia can, according to the synchrony of the culture in which it occurs, have one function or another.

As an example I shall take the strange heterotopia of the cemetery. The cemetery is certainly a place unlike ordinary cultural spaces. It is a space that is however connected with all the sites of the city, state or society or village, etc., since each individual, each family has relatives in the cemetery. In western culture the cemetery has practically always existed. But it has undergone important changes. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the cemetery was placed at the heart of the city, next to the church. In it there was a hierarchy of possible tombs. There was the charnel house in which bodies lost the last traces of individuality, there were a few individual tombs and then there were the tombs inside the church. These latter tombs were themselves of two types, either simply tombstones with an inscription, or mausoleums with statues. This cemetery housed inside the sacred space of the church has taken on a quite different cast in modern civilizations, and curiously, it is in a time when civilization has become "atheistic," as one says very crudely, that western culture has established what is termed the cult of the dead.

Basically it was quite natural that, in a time of real belief in the resurrection of bodies and the immortality of the soul, overriding importance was not accorded to the body's remains. On the contrary, from the moment when people are no longer sure that they have a soul or that the body will regain life, it is perhaps necessary to give much more attention to the dead body, which is ultimately the only trace of our existence in the world and in language. In any case, it is from the beginning of the nineteenth century that everyone has a right to her or his own little box for her or his own little personal decay, but on the other hand, it is only from that start of the nineteenth century that cemeteries began to be located at the outside border of cities. In correlation with the individualization of death and the bourgeois appropriation of the cemetery, there arises an obsession with death as an "illness." The dead, it is supposed, bring illnesses to the living, and it is the presence and proximity of the dead right beside the houses, next to the church, almost in the middle of the street, it is this proximity that propagates death itself. This major theme of illness spread by the contagion in the cemeteries persisted until the end of the eighteenth century, until, during the nineteenth century, the shift of cemeteries toward the suburbs was initiated. The cemeteries then came to constitute, no longer the sacred and immortal heart of the city, but the other city, where each family possesses its dark resting place.

Third principle. The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible. Thus it is that the theater brings onto the rectangle of the stage, one after the other, a whole series of places that are foreign to one another; thus it is that the cinema is a very odd rectangular room, at the end of which, on a two-dimensional screen, one sees the projection of a three-dimensional space, but perhaps the oldest example of these heterotopias that take the form of contradictory sites is the garden. We must not forget that in the Orient the garden, an astonishing creation that is now a thousand years old, had very deep and seemingly superimposed meanings. The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others that were like an umbilicus, the navel of the world at its center (the basin and water fountain were there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in this sort of microcosm. As for carpets, they were originally reproductions of gardens (the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space). The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world. The garden has been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia since the beginnings of antiquity (our modern zoological gardens spring from that source).

Fourth principle. Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time — which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies. The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time. This situation shows us that the cemetery is indeed a highly heterotopic place since, for the individual, the cemetery begins with this strange heterochrony, the loss of life, and with this quasi-eternity in which her permanent lot is dissolution and disappearance.

From a general standpoint, in a society like ours heterotopias and heterochronies are structured and distributed in a relatively complex fashion. First of all, there are heterotopias of indefinitely accumulating time, for example museums and libraries, Museums and libraries have become heterotopias in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit, whereas in the seventeenth century, even at the end of the century, museums and libraries were the expression of an individual choice. By contrast, the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity. The museum and the library are heterotopias that are proper to western culture of the nineteenth century.

Opposite these heterotopias that are linked to the accumulation of time, there are those linked, on the contrary, to time in its most flowing, transitory, precarious aspect, to time in the mode of the festival. These heterotopias are not oriented toward the eternal, they are rather absolutely temporal [chroniques]. Such, for example, are the fairgrounds, these "marvelous empty sites on the outskirts of cities" that teem once or twice a year with stands, displays, heteroclite objects, wrestlers, snakewomen, fortune-tellers, and so forth. Quite recently, a new kind of temporal heterotopia has been invented: vacation villages, such as those Polynesian villages that offer a compact three weeks of primitive and eternal nudity to the inhabitants of the cities. You see, moreover, that through the two forms of heterotopias that come together here, the heterotopia of the festival and that of the eternity of accumulating time, the huts of Djerba are in a sense relatives of libraries and museums. for the rediscovery of Polynesian life abolishes time; yet the experience is just as much the,, rediscovery of time, it is as if the entire history of humanity reaching back to its origin were accessible in a sort of immediate knowledge,

Fifth principle. Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications. To get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures. Moreover, there are even heterotopias that are entirely consecrated to these activities of purification —purification that is partly religious and partly hygienic, such as the hammin of the Moslems, or else purification that appears to be purely hygienic, as in Scandinavian saunas

.

There are others, on the contrary, that seem to be pure and simple openings, but that generally hide curious exclusions. Everyone can enter into thew heterotopic sites, but in fact that is only an illusion— we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded. I am thinking for example, of the famous bedrooms that existed on the great farms of Brazil and elsewhere in South America. The entry door did not lead into the central room where the family lived, and every individual or traveler who came by had the right to ope this door, to enter into the bedroom and to sleep there for a night. Now these bedrooms were such that the individual who went into them never had access to the family's quarter the visitor was absolutely the guest in transit, was not really the invited guest. This type of heterotopia, which has practically disappeared from our civilizations, could perhaps be found in the famous American motel rooms where a man goes with his car and his mistress and where illicit sex is both absolutely sheltered and absolutely hidden, kept isolated without however being allowed out in the open.

Sixth principle. The last trait of heterotopias is that they have a function in relation to all the space that remains. This function unfolds between two extreme poles. Either their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory (perhaps that is the role that was played by those famous brothels of which we are now deprived). Or else, on the contrary, their role is to create a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled. This latter type would be the heterotopia, not of illusion, but of compensation, and I wonder if certain colonies have not functioned somewhat in this manner. In certain cases, they have played, on the level of the general organization of terrestrial space, the role of heterotopias. I am thinking, for example, of the first wave of colonization in the seventeenth century, of the Puritan societies that the English had founded in America and that were absolutely perfect other places. I am also thinking of those extraordinary Jesuit colonies that were founded in South America: marvelous, absolutely regulated colonies in which human perfection was effectively achieved. The Jesuits of Paraguay established colonies in which existence was regulated at every turn. The village was laid out according to a rigorous plan around a rectangular place at the foot of which was the church; on one side, there was the school; on the other, the cemetery, and then, in front of the church, an avenue set out that another crossed at fight angles; each family had its little cabin along these two axes and thus the sign of Christ was exactly reproduced. Christianity marked the space and geography of the American world with its fundamental sign.

The daily life of individuals was regulated, not by the whistle, but by the bell. Everyone was awakened at the same time, everyone began work at the same time; meals were at noon and five o'clock, then came bedtime, and at midnight came what was called the marital wake-up, that is, at the chime of the churchbell, each person carried out her/his duty.

Brothels and colonies are two extreme types of heterotopia, and if we think, after all, that the boat is a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea and that, from port to port, from tack to tack, from brothel to brothel, it goes as far as the colonies in search of the most precious treasures they conceal in their gardens, you will understand why the boat has not only been for our civilization, from the sixteenth century until the present, the great instrument of economic development (I have not been speaking of that today), but has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination. The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.

Yet it is necessary to notice that the space which today appears to form the horizon of our concerns, our theory, our systems, is not an innovation; space itself has a history in Western experience, and it is not possible to disregard the fatal intersection of time with space. One could say, by way of retracing this history of space very roughly, that in the Middle Ages there was a hierarchic ensemble of places: sacred places and profane plates: protected places and open, exposed places: urban places and rural places (all these concern the real life of men). In cosmological theory, there were the supercelestial places as opposed to the celestial, and the celestial place was in its turn opposed to the terrestrial place. There were places where things had been put because they had been violently displaced, and then on the contrary places where things found their natural ground and stability. It was this complete hierarchy, this opposition, this intersection of places that constituted what could very roughly be called medieval space: the space of emplacement.

This space of emplacement was opened up by Galileo. For the real scandal of Galileo's work lay not so much in his discovery, or rediscovery, that the earth revolved around the sun, but in his constitution of an infinite, and infinitely open space. In such a space the place of the Middle Ages turned out to be dissolved. as it were; a thing's place was no longer anything but a point in its movement, just as the stability of a thing was only its movement indefinitely slowed down. In other words, starting with Galileo and the seventeenth century, extension was substituted for emplacement.

Today the site has been substituted for extension which itself had replaced emplacement. The site is defined by relations of proximity between points or elements; formally, we can describe these relations as series, trees, or grids. Moreover, the importance of the site as a problem in contemporary technical work is well known: the storage of data or of the intermediate results of a calculation in the memory of a machine, the circulation of discrete elements with a random output (automobile traffic is a simple case, or indeed the sounds on a telephone line); the identification of marked or coded elements inside a set that may be randomly distributed, or may be arranged according to single or to multiple classifications.

In a still more concrete manner, the problem of siting or placement arises for mankind in terms of demography. This problem of the human site or living space is not simply that of knowing whether there will be enough space for men in the world —a problem that is certainly quite important — but also that of knowing what relations of propinquity, what type of storage, circulation, marking, and classification of human elements should be adopted in a given situation in order to achieve a given end. Our epoch is one in which space takes for us the form of relations among sites.

In any case I believe that the anxiety of our era has to do fundamentally with space, no doubt a great deal more than with time. Time probably appears to us only as one of the various distributive operations that are possible for the elements that are spread out in space,

Now, despite all the techniques for appropriating space, despite the whole network of knowledge that enables us to delimit or to formalize it, contemporary space is perhaps still not entirely desanctified (apparently unlike time, it would seem, which was detached from the sacred in the nineteenth century). To be sure a certain theoretical desanctification of space (the one signaled by Galileo's work) has occurred, but we may still not have reached the point of a practical desanctification of space. And perhaps our life is still governed by a certain number of oppositions that remain inviolable, that our institutions and practices have not yet dared to break down. These are oppositions that we regard as simple givens: for example between private space and public space, between family space and social space, between cultural space and useful space, between the space of leisure and that of work. All these are still nurtured by the hidden presence of the sacred.

Bachelard's monumental work and the descriptions of phenomenologists have taught us that we do not live in a homogeneous and empty space, but on the contrary in a space thoroughly imbued with quantities and perhaps thoroughly fantasmatic as well. The space of our primary perception, the space of our dreams and that of our passions hold within themselves qualities that seem intrinsic: there is a light, ethereal, transparent space, or again a dark, rough, encumbered space; a space from above, of summits, or on the contrary a space from below of mud; or again a space that can be flowing like sparkling water, or space that is fixed, congealed, like stone or crystal. Yet these analyses, while fundamental for reflection in our time, primarily concern internal space. I should like to speak now of external space.

The space in which we live, which draws us out of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives. our time and our history occurs, the space that claws and gnaws at us, is also, in itself, a heterogeneous space. In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another.

Of course one might attempt to describe these different sites by looking for the set of relations by which a given site can be defined. For example, describing the set of relations that define the sites of transportation, streets, trains (a train is an extraordinary bundle of relations because it is something through which one goes, it is also something by means of which one can go from one point to another, and then it is also something that goes by). One could describe, via the cluster of relations that allows them to be defined, the sites of temporary relaxation —cafes, cinemas, beaches. Likewise one could describe, via its network of relations, the closed or semi-closed sites of rest — the house, the bedroom, the bed, el cetera. But among all these sites, I am interested in certain ones that have the curious property of being in relation with all the other sites, but in such a way as to suspect, neutralize, or invert the set of relations that they happen to designate, mirror, or reflect. These spaces, as it were, which are linked with all the others, which however contradict all the other sites, are of two main types.

HETEROTOPIAS

First there are the utopias. Utopias are sites with no real place. They are sites that have a general relation of direct or inverted analogy with the real space of Society. They present society itself in a perfected form, or else society turned upside down, but in any case these utopias are fundamentally unreal spaces.

There are also, probably in every culture, in every civilization, real places — places that do exist and that are formed in the very founding of society — which are something like counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted. Places of this kind are outside of all places, even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality. Because these places are absolutely different from all the sites that they reflect and speak about, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias. I believe that between utopias and these quite other sites, these heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself there where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space that opens up behind the surface; I am over there, there where I am not, a sort of shadow that gives my own visibility to myself, that enables me to see myself there where I am absent: such is the utopia of the mirror. But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror does exist in reality, where it exerts a sort of counteraction on the position that I occupy. From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see myself over there. Starting from this gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place that I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.

As for the heterotopias as such, how can they be described? What meaning do they have? We might imagine a sort of systematic description — I do not say a science because the term is too galvanized now —that would, in a given society, take as its object the study, analysis, description, and "reading" (as some like to say nowadays) of these different spaces, of these other places. As a sort of simultaneously mythic and real contestation of the space in which we live, this description could be called heterotopology.

Its first principle is that there is probably not a single culture in the world that fails to constitute heterotopias. That is a constant of every human group. But the heterotopias obviously take quite varied forms, and perhaps no one absolutely universal form of heterotopia would be found. We can however class them in two main categories.

In the so-called primitive societies, there is a certain form of heterotopia that I would call crisis heterotopias, i.e., there are privileged or sacred or forbidden places, reserved for individuals who are, in relation to society and to the human environment in which they live, in a state of crisis: adolescents, menstruating women, pregnant women. the elderly, etc. In out society, these crisis heterotopias are persistently disappearing, though a few remnants can still be found. For example, the boarding school, in its nineteenth-century form, or military service for young men, have certainly played such a role, as the first manifestations of sexual virility were in fact supposed to take place "elsewhere" than at home. For girls, there was, until the middle of the twentieth century, a tradition called the "honeymoon trip" which was an ancestral theme. The young woman's deflowering could take place "nowhere" and, at the moment of its occurrence the train or honeymoon hotel was indeed the place of this nowhere, this heterotopia without geographical markers.

But these heterotopias of crisis are disappearing today and are being replaced, I believe, by what we might call heterotopias of deviation: those in which individuals whose behavior is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm are placed. Cases of this are rest homes and psychiatric hospitals, and of course prisons, and one should perhaps add retirement homes that are, as it were, on the borderline between the heterotopia of crisis and the heterotopia of deviation since, after all, old age is a crisis, but is also a deviation since in our society where leisure is the rule, idleness is a sort of deviation.

The second principle of this description of heterotopias is that a society, as its history unfolds, can make an existing heterotopia function in a very different fashion; for each heterotopia has a precise and determined function within a society and the same heterotopia can, according to the synchrony of the culture in which it occurs, have one function or another.

As an example I shall take the strange heterotopia of the cemetery. The cemetery is certainly a place unlike ordinary cultural spaces. It is a space that is however connected with all the sites of the city, state or society or village, etc., since each individual, each family has relatives in the cemetery. In western culture the cemetery has practically always existed. But it has undergone important changes. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the cemetery was placed at the heart of the city, next to the church. In it there was a hierarchy of possible tombs. There was the charnel house in which bodies lost the last traces of individuality, there were a few individual tombs and then there were the tombs inside the church. These latter tombs were themselves of two types, either simply tombstones with an inscription, or mausoleums with statues. This cemetery housed inside the sacred space of the church has taken on a quite different cast in modern civilizations, and curiously, it is in a time when civilization has become "atheistic," as one says very crudely, that western culture has established what is termed the cult of the dead.

Basically it was quite natural that, in a time of real belief in the resurrection of bodies and the immortality of the soul, overriding importance was not accorded to the body's remains. On the contrary, from the moment when people are no longer sure that they have a soul or that the body will regain life, it is perhaps necessary to give much more attention to the dead body, which is ultimately the only trace of our existence in the world and in language. In any case, it is from the beginning of the nineteenth century that everyone has a right to her or his own little box for her or his own little personal decay, but on the other hand, it is only from that start of the nineteenth century that cemeteries began to be located at the outside border of cities. In correlation with the individualization of death and the bourgeois appropriation of the cemetery, there arises an obsession with death as an "illness." The dead, it is supposed, bring illnesses to the living, and it is the presence and proximity of the dead right beside the houses, next to the church, almost in the middle of the street, it is this proximity that propagates death itself. This major theme of illness spread by the contagion in the cemeteries persisted until the end of the eighteenth century, until, during the nineteenth century, the shift of cemeteries toward the suburbs was initiated. The cemeteries then came to constitute, no longer the sacred and immortal heart of the city, but the other city, where each family possesses its dark resting place.

Third principle. The heterotopia is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible. Thus it is that the theater brings onto the rectangle of the stage, one after the other, a whole series of places that are foreign to one another; thus it is that the cinema is a very odd rectangular room, at the end of which, on a two-dimensional screen, one sees the projection of a three-dimensional space, but perhaps the oldest example of these heterotopias that take the form of contradictory sites is the garden. We must not forget that in the Orient the garden, an astonishing creation that is now a thousand years old, had very deep and seemingly superimposed meanings. The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others that were like an umbilicus, the navel of the world at its center (the basin and water fountain were there); and all the vegetation of the garden was supposed to come together in this space, in this sort of microcosm. As for carpets, they were originally reproductions of gardens (the garden is a rug onto which the whole world comes to enact its symbolic perfection, and the rug is a sort of garden that can move across space). The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world. The garden has been a sort of happy, universalizing heterotopia since the beginnings of antiquity (our modern zoological gardens spring from that source).

Fourth principle. Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time — which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies. The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time. This situation shows us that the cemetery is indeed a highly heterotopic place since, for the individual, the cemetery begins with this strange heterochrony, the loss of life, and with this quasi-eternity in which her permanent lot is dissolution and disappearance.

From a general standpoint, in a society like ours heterotopias and heterochronies are structured and distributed in a relatively complex fashion. First of all, there are heterotopias of indefinitely accumulating time, for example museums and libraries, Museums and libraries have become heterotopias in which time never stops building up and topping its own summit, whereas in the seventeenth century, even at the end of the century, museums and libraries were the expression of an individual choice. By contrast, the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity. The museum and the library are heterotopias that are proper to western culture of the nineteenth century.

Opposite these heterotopias that are linked to the accumulation of time, there are those linked, on the contrary, to time in its most flowing, transitory, precarious aspect, to time in the mode of the festival. These heterotopias are not oriented toward the eternal, they are rather absolutely temporal [chroniques]. Such, for example, are the fairgrounds, these "marvelous empty sites on the outskirts of cities" that teem once or twice a year with stands, displays, heteroclite objects, wrestlers, snakewomen, fortune-tellers, and so forth. Quite recently, a new kind of temporal heterotopia has been invented: vacation villages, such as those Polynesian villages that offer a compact three weeks of primitive and eternal nudity to the inhabitants of the cities. You see, moreover, that through the two forms of heterotopias that come together here, the heterotopia of the festival and that of the eternity of accumulating time, the huts of Djerba are in a sense relatives of libraries and museums. for the rediscovery of Polynesian life abolishes time; yet the experience is just as much the,, rediscovery of time, it is as if the entire history of humanity reaching back to its origin were accessible in a sort of immediate knowledge,

Fifth principle. Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications. To get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures. Moreover, there are even heterotopias that are entirely consecrated to these activities of purification —purification that is partly religious and partly hygienic, such as the hammin of the Moslems, or else purification that appears to be purely hygienic, as in Scandinavian saunas

.

There are others, on the contrary, that seem to be pure and simple openings, but that generally hide curious exclusions. Everyone can enter into thew heterotopic sites, but in fact that is only an illusion— we think we enter where we are, by the very fact that we enter, excluded. I am thinking for example, of the famous bedrooms that existed on the great farms of Brazil and elsewhere in South America. The entry door did not lead into the central room where the family lived, and every individual or traveler who came by had the right to ope this door, to enter into the bedroom and to sleep there for a night. Now these bedrooms were such that the individual who went into them never had access to the family's quarter the visitor was absolutely the guest in transit, was not really the invited guest. This type of heterotopia, which has practically disappeared from our civilizations, could perhaps be found in the famous American motel rooms where a man goes with his car and his mistress and where illicit sex is both absolutely sheltered and absolutely hidden, kept isolated without however being allowed out in the open.

Sixth principle. The last trait of heterotopias is that they have a function in relation to all the space that remains. This function unfolds between two extreme poles. Either their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory (perhaps that is the role that was played by those famous brothels of which we are now deprived). Or else, on the contrary, their role is to create a space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled. This latter type would be the heterotopia, not of illusion, but of compensation, and I wonder if certain colonies have not functioned somewhat in this manner. In certain cases, they have played, on the level of the general organization of terrestrial space, the role of heterotopias. I am thinking, for example, of the first wave of colonization in the seventeenth century, of the Puritan societies that the English had founded in America and that were absolutely perfect other places. I am also thinking of those extraordinary Jesuit colonies that were founded in South America: marvelous, absolutely regulated colonies in which human perfection was effectively achieved. The Jesuits of Paraguay established colonies in which existence was regulated at every turn. The village was laid out according to a rigorous plan around a rectangular place at the foot of which was the church; on one side, there was the school; on the other, the cemetery, and then, in front of the church, an avenue set out that another crossed at fight angles; each family had its little cabin along these two axes and thus the sign of Christ was exactly reproduced. Christianity marked the space and geography of the American world with its fundamental sign.

The daily life of individuals was regulated, not by the whistle, but by the bell. Everyone was awakened at the same time, everyone began work at the same time; meals were at noon and five o'clock, then came bedtime, and at midnight came what was called the marital wake-up, that is, at the chime of the churchbell, each person carried out her/his duty.

Brothels and colonies are two extreme types of heterotopia, and if we think, after all, that the boat is a floating piece of space, a place without a place, that exists by itself, that is closed in on itself and at the same time is given over to the infinity of the sea and that, from port to port, from tack to tack, from brothel to brothel, it goes as far as the colonies in search of the most precious treasures they conceal in their gardens, you will understand why the boat has not only been for our civilization, from the sixteenth century until the present, the great instrument of economic development (I have not been speaking of that today), but has been simultaneously the greatest reserve of the imagination. The ship is the heterotopia par excellence. In civilizations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.

Sunday, 21 April 2013

Tuesday, 9 April 2013

Now this is what I call a press release

SOME FEELING IN THE BELLIES OF THE TANKERS WHO PASS US MAKING SAD MANIC BONGS LIKE DRUMS

Still at twilight something blurs over your shoulder.

Which is it?

It’s prickly.

We have made some decisions.

We want to fail more, act without authority.

Plus there’s something phlegmatic about the world state don’t you think?

There’s a blood system promoting biology as destiny.

A series of patriarchies that’s a problem to the Nth degree.

What about hyper-capitalism, this homicidal class system, the school system that’s kaput?

Then there are castles everywhere—look at them fake tanning and signing autographs!

At least there’s one thing we stand behind.

There’s still an ecosystem right? And here’s this sound system.

We dusted it off. Electronic is just one place in the body. We went temporarily acoustic.

We made our own instruments. We took an old bedspring, a microphone and:

“Stay out here…”

Now we’re bending our voices to sound like Emily R., who recorded the track on her cellphone speaker.

10 more! We say to him. Get shaking!

Our walk gets longer. It’s a walk in the panpipes of the body. We come to the edge. So much water. The ocean is twice its original size. We take a bunch of surveys.They know everything about us. We don’t buy what they say. We take a heap of estrogen. All around us things are howling and then we stand on the pier end. The light is pink and green and pink and green. It reminds us of home—like we imagine it could be. But when the color pancakes out over the horizon, we don’t know what we’re looking at. That’s ok. This time it’s structural.

No habits!

Everybody is always desiring already imagined things.

When we travel between thresholds, people say: “you’re hiding.”

Not everything can be so easily explained.

When we travel between thresholds, people say: “you’re hiding.”

Not everything can be so easily explained.

We have a bellyache, a big stink, a major grouse or two with manufactured knowledge.

But how do you build an album about not knowing?

Now your voice is in my throat, floating there…

Often people take pills for these things.

To us the body is no longer psychological.

It’s certainly not a container, we don’t believe in metaphors.

Like dog/wolf—there aren’t many anymore.

But how do you build an album about not knowing?

Now your voice is in my throat, floating there…

Often people take pills for these things.

To us the body is no longer psychological.

It’s certainly not a container, we don’t believe in metaphors.

Like dog/wolf—there aren’t many anymore.

Still at twilight something blurs over your shoulder.

Which is it?

It’s prickly.

Our hair is out.

We have made some decisions.

We want to fail more, act without authority.

Plus there’s something phlegmatic about the world state don’t you think?

There’s a blood system promoting biology as destiny.

A series of patriarchies that’s a problem to the Nth degree.

What about hyper-capitalism, this homicidal class system, the school system that’s kaput?

Then there are castles everywhere—look at them fake tanning and signing autographs!

At least there’s one thing we stand behind.

There’s still an ecosystem right? And here’s this sound system.

We dusted it off. Electronic is just one place in the body. We went temporarily acoustic.

We made our own instruments. We took an old bedspring, a microphone and:

“Stay out here…”

Now we’re bending our voices to sound like Emily R., who recorded the track on her cellphone speaker.

No habits!

There are other ways to do things.

There are other ways to do things.

Still sometimes it all seems so bad.

Don’t worry we won’t commit Harakiri, stomach cutting or anything like it.

The honor system is corrupt, just another privilege.

Like how it’s a privilege to make an album, to move freely.

Don’t worry we won’t commit Harakiri, stomach cutting or anything like it.

The honor system is corrupt, just another privilege.

Like how it’s a privilege to make an album, to move freely.

We just have to go faster we mean breakneck we mean “like crazy.”

How at 5am that warehouse beat is coming up like sour steam.

All over the dance floor we’re asking: can this DNA turn into something else?

It’s not metaphorical. It’s explicit.

There are surgeries and fantasies and holes sweating through the wall.

It’s a question about feelings. It’s a question about who gets to risk.

All over the dance floor we’re asking: can this DNA turn into something else?

It’s not metaphorical. It’s explicit.

There are surgeries and fantasies and holes sweating through the wall.

It’s a question about feelings. It’s a question about who gets to risk.

But things don’t change so easily.

There’s still Monsanto, fracking and “terminator seeds.”

Every morning we wake up wondering: who’s kicking who on the street corner?

There’s still Monsanto, fracking and “terminator seeds.”

Every morning we wake up wondering: who’s kicking who on the street corner?

Now we have to start. We choose process over everything else.

Letting go of outcomes is another privilege.

Keep it lateral.

We ask our friends to help.

Letting go of outcomes is another privilege.

Keep it lateral.

We ask our friends to help.

Together we leave the village and walk down the road. The light starts exercising itself. The old sun is out in his winter jumpsuit doing sit-ups and squat thrusts between the nettles and moldy brush.

10 more! We say to him. Get shaking!

Our walk gets longer. It’s a walk in the panpipes of the body. We come to the edge. So much water. The ocean is twice its original size. We take a bunch of surveys.They know everything about us. We don’t buy what they say. We take a heap of estrogen. All around us things are howling and then we stand on the pier end. The light is pink and green and pink and green. It reminds us of home—like we imagine it could be. But when the color pancakes out over the horizon, we don’t know what we’re looking at. That’s ok. This time it’s structural.

No habits!

Of course we’re growing restless.

Sunday, 3 March 2013

Tuesday, 19 February 2013

Silky death tastes sweet and square

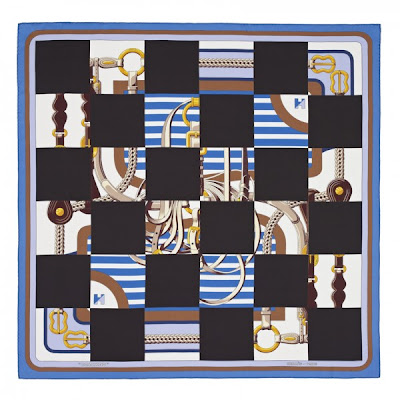

I tweeted about these babies the other day but I can't get enough of them.

They're just so pretty.

If you don't know what you're looking at, it's the inaugural range of Commes de Carrés scarves.

Comme des Garçons x Hermès. Yes, you read right. Comme des Garçons and Hermès designed a range of silk scarves together.

The pegasus one is my fave.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)